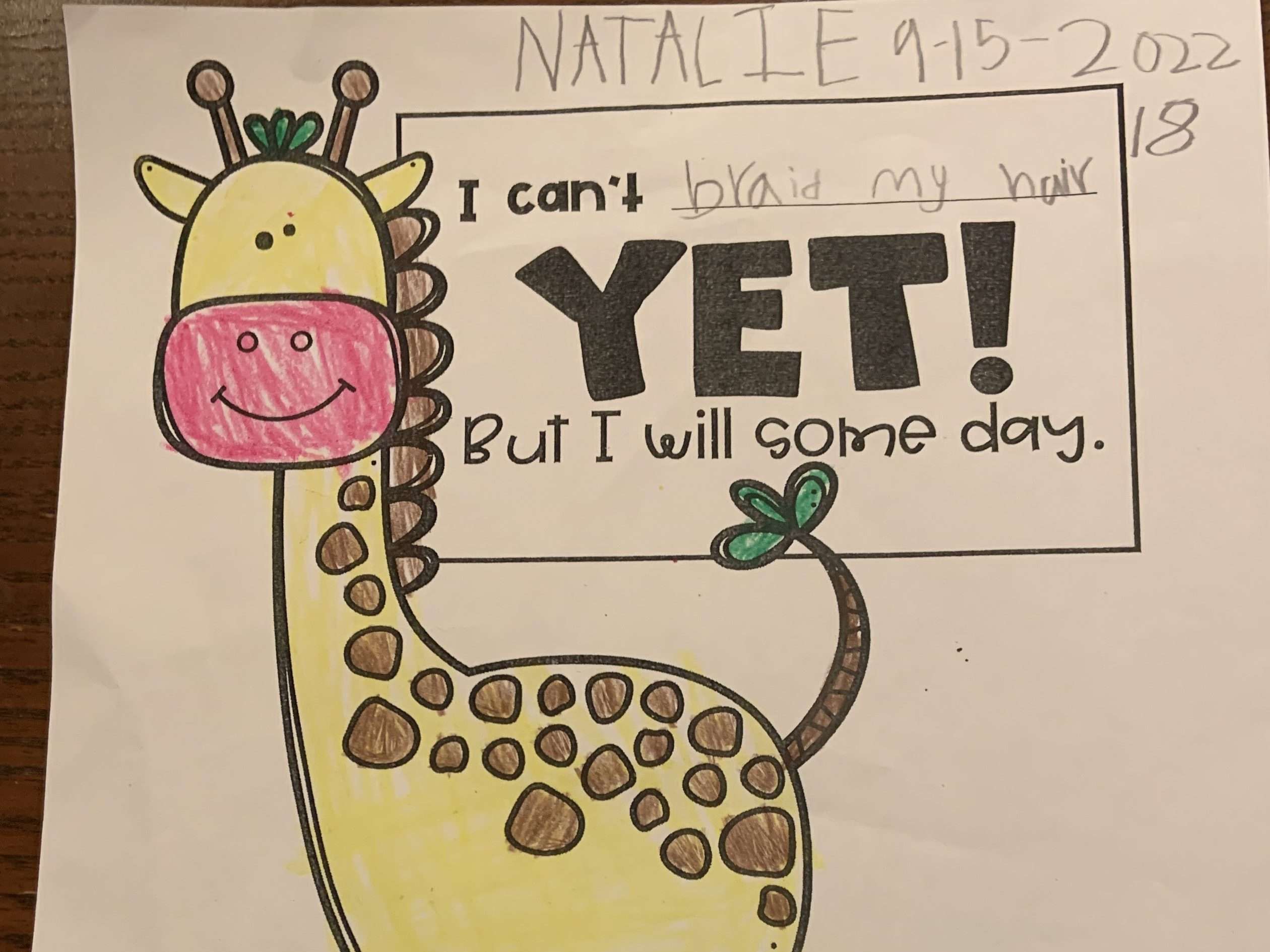

During one of the first weeks of school, my daughter came home from first grade with this paper in her backpack:

I was thrilled to see her teachers reinforcing a belief we’ve been working on instilling at home: that even though there are a lot of things she can do now that she’s older, some things will still feel hard or even impossible when she first tries them.

As an adult, it’s easy to see how some of the expectations kids have are unreasonable. No one is born knowing how to ride a bike, or braid their hair, or spell pterodactyl. Trying and failing are not simply normal parts of the learning process, but necessary ones. After all, the only people who never make mistakes and experience failure are those who never learn anything new.

In this context, struggle and failure become something to be encouraged and celebrated, rather than avoided. When my daughter shakily pedals her bike without training wheels as I hold onto the back, it’s obvious that my job as a parent is not to say, “Wow, you’re not very good at this, are you? You should just go back to training wheels,” or to let go of the bike at the top of a hill while shouting, “All the other kids have already learned how to do this!” or “What’s meant to be will be!”

But no matter how much we encourage kids to persevere through challenges, adults tend to apply a different set of expectations to ourselves. Subconsciously, it can be easy to think we should eventually grow out of this learning phase or that we should feel ashamed when we still experience failure. You may have these critical thoughts while drafting (“Wow, this draft is not very good, is it? Maybe I should stop trying.”). Or maybe these thoughts pop up when you receive feedback (“Wow, there are still so many areas to work on. Shouldn’t I be done by now?”) or when you face publishing’s unpredictable and often unfair frustrations (“Wow, ten rejections in a row. Maybe it’s not meant to be.”).

First, while it may not be possible to completely eradicate these thoughts, it can help to examine them. Even if you’re unable to celebrate challenges and failures, you might try reframing your thoughts to acknowledge their importance. Maybe that means shifting your thoughts while drafting (“This draft is not as good as a published book . . . yet; I’m still exploring the story and learning about the characters.”). Or shifting your thoughts while revising and receiving feedback (“These revisions aren’t finished . . . yet; identifying areas to work on is necessary for revising and making this book stronger.”). Or shifting your thoughts during other stages of the writing and publishing process (“That author found an agent and I haven’t . . . yet; while I can’t control agents’ responses, the next step in my control is working on my new book idea/sharing my draft for feedback/polishing my query letter/submitting my next round of queries/etc.”).

Second, consider connecting with other writers. Finding your creative community can help to put the struggles you face into perspective, and can remind you that you’re far from alone—every author at every stage of their career experiences self-doubts; struggles with difficult drafts and revisions; and receives painful rejections.

Lastly, as I mentioned in my letter about rejection, remember to celebrate your wins. The flip side of every challenge you face is the eventual achievement of overcoming it. When you have a new book idea, finish a first draft, complete a difficult revision, share your work for feedback, draft a query letter, or reach any other creative milestone, try to find a way to share and celebrate it. Taking the time to acknowledge these successes will help to refill your creative well and reinvigorate you as you set your sights on your next goal.

Your Editor Friend,

Julie